Meet ‘Sue’, The 444-Million-Year-Old Fossil That Preserved Everything – The Daily Galaxy

2025-04-22T18:00:00Z

It has no shell, no limbs—and yet, it may be the best-preserved ancient creature ever found. What happened to ‘Sue’?

A newly identified fossil discovered in the ancient shale of South Africa, has stunned paleontologists with its rare preservation of internal soft tissues. The research, published in Papers in Palaeontology on March 26, 2025, details an extraordinary 25-year study.

Sue, An Unprecedented Window Into Ancient Arthropods

The fossil, affectionately nicknamed “Sue”, presents a biological paradox: the external features — such as the carapace, legs, and head — typically preserved in the fossil record, are entirely missing.

Instead, the fossil offers an “inside-out” view of an early arthropod’s muscles, tendons, connective tissues, and even gut structures, astonishingly well-preserved in sediment nearly half a billion years old.

This type of preservation is almost unheard of. In modern paleontology, soft tissue fossilization is exceptionally rare due to the fragility of organic matter. Yet in this case, the internal structures endured while the typically more resilient exoskeleton decayed — a reversal of natural fossilization trends.

The Toxic Grave That Preserved a Wonder

The fossil was unearthed in the Soom Shale, a sedimentary formation located roughly 250 miles north of Cape Town, South Africa. This marine basin formed just after a catastrophic glaciation event during the Ordovician period, which led to one of the five major mass extinctions, wiping out 85% of Earth’s species.

This particular basin seems to have served as a refuge for a unique community of marine organisms. Its highly toxic, anoxic (oxygen-deprived) and hydrogen sulfide-rich waters likely enabled the fossil’s unique preservation. Scientists speculate that the chemistry of this environment acted like a preservative vault, mineralizing internal tissues before they could decay.

Such conditions may have triggered a form of chemical fossilization rarely seen on Earth, a process still not fully understood. Researchers describe it as a “strange chemical alchemy” — one that preserved Sue’s innards in exquisite detail.

A Fossil With No Known Equal

Despite its detailed preservation, Keurbos susanae doesn’t neatly fit into any known lineage. It’s clearly an early marine arthropod, but its precise evolutionary relationships remain a mystery.

Professor Gabbott refers to Sue as a “headless, legless wonder,” not only because those body parts are missing, but also because the fossil refuses to be easily categorized. In a fossil record rich with arthropods, this specimen flips expectations by preserving the least expected parts of the body.

A Legacy Fossil and a Personal Tribute

Professor Sarah Gabbott began studying this fossil 25 years ago, at the beginning of her academic career. The decision to name the fossil after her mother, Sue, adds a personal dimension to the discovery.

“I tell my mom in jest that I named the fossil Sue after her because she is a well-preserved specimen,” Gabbott said, “but in truth, I named her Sue because my mom always said I should follow a career that makes me happy — whatever that may be.”

The naming of Keurbos susanae is more than a nod to maternal inspiration — it’s the culmination of decades of work, persistence, and passion for ancient life.

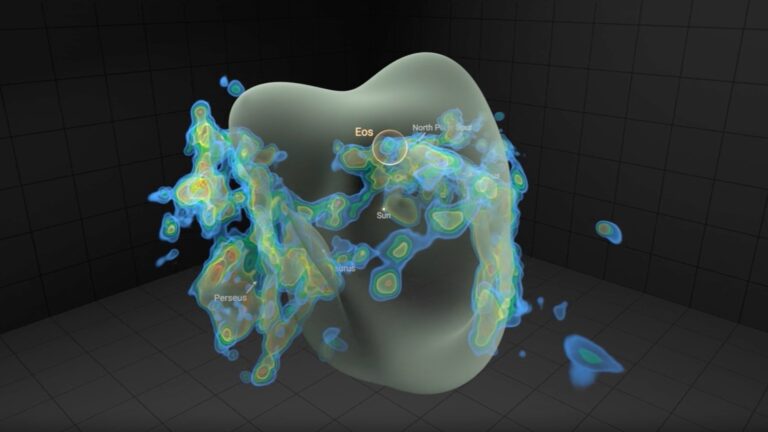

The fossil Keurbos susanae, or Sue, in the rock. Credit: University of Leicester

The Bigger Picture for Evolutionary Biology

Arthropods make up around 85% of all animal species, including insects, spiders, lobsters, and crabs. Their fossil history stretches back over 500 million years, but examples like Sue offer something radically different — a peek beneath the exoskeleton into how these creatures functioned internally.

This kind of preservation gives scientists a rare chance to study the myoanatomy (muscle arrangement) and endoskeletal structures of early marine arthropods. It may eventually help researchers untangle parts of the arthropod evolutionary tree that remain obscure, filling in gaps that more conventional fossils can’t address.

Auto-posted from news source