One Orbit, One Everest Lost: A Planet Evaporates Into a 9-Million-Kilometer Tail – SciTechDaily

2025-04-24T08:24:39Z

Astronomers from MIT have uncovered a dramatic celestial spectacle: a Mercury-sized exoplanet that is rapidly disintegrating as it orbits perilously close to its star. The small and rocky lava world sheds an amount of material equivalent to the mass of Mount …

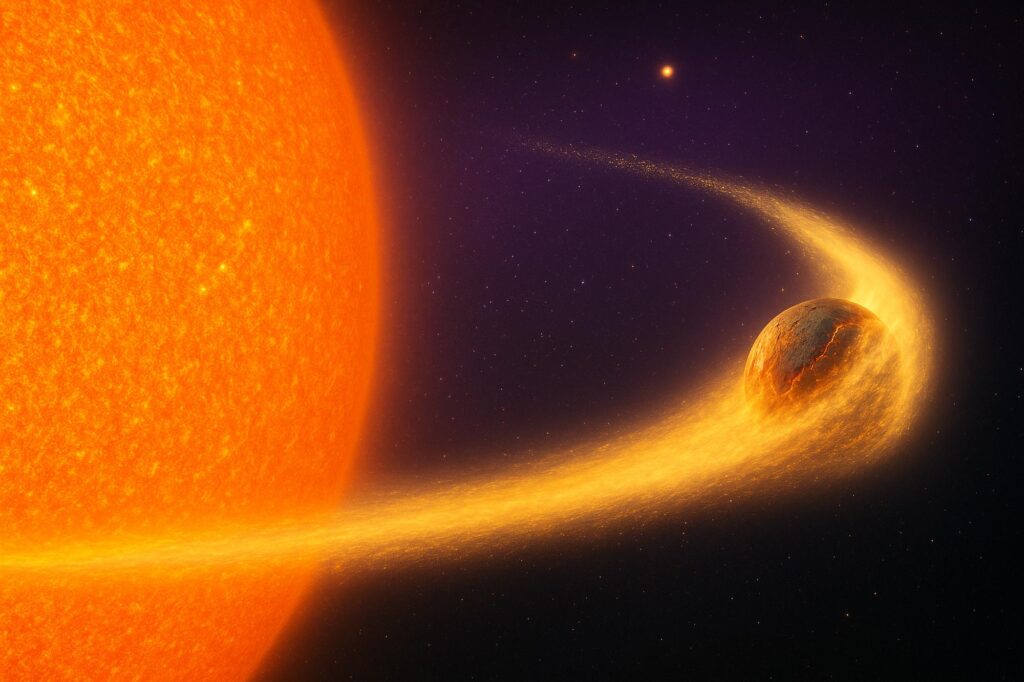

Astronomers from MIT have uncovered a dramatic celestial spectacle: a Mercury-sized exoplanet that is rapidly disintegrating as it orbits perilously close to its star. The small and rocky lava world sheds an amount of material equivalent to the mass of Mount Everest every 30.5 hours.

The planet, located 140 light-years away, completes an orbit every 30.5 hours, resulting in intense heat that causes its surface to boil and stream into space. Detected by NASA’s TESS mission, this crumbling world trails a massive, comet-like tail of minerals, revealing a rare opportunity to observe a planet in its final throes.

Discovery of a Dying Planet

MIT astronomers have discovered a planet, about 140 light-years from Earth, that is rapidly falling apart.

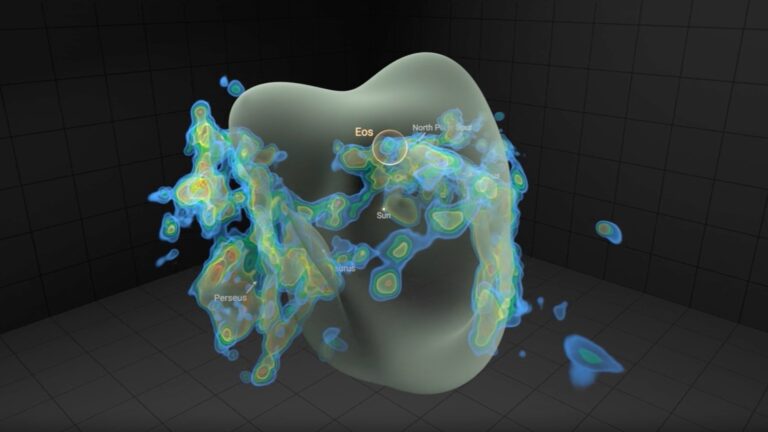

The disintegrating world is roughly the size of Mercury but orbits its star at an extremely close distance, about 20 times closer than Mercury is to our sun. It completes a full orbit in just 30.5 hours. Because of this intense proximity, the planet’s surface is likely molten, with magma boiling off into space. As it races around its star, it loses vast amounts of rocky material, continually evaporating away.

A Strange Signal from TESS

Researchers spotted the planet using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), an MIT-led mission that watches nearby stars for brief dips in brightness, signals that can indicate a planet passing in front of its star. In this case, the dip in light wasn’t consistent; it varied in depth with each orbit, which caught the scientists’ attention.

They determined that the signal came from a rocky planet orbiting very close to its star, leaving behind a long trail of debris similar to a comet’s tail.

“The extent of the tail is gargantuan, stretching up to 9 million kilometers long, or roughly half of the planet’s entire orbit,” says Marc Hon, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.

Dramatic Disintegration in Progress

It appears that the planet is disintegrating at a dramatic rate, shedding an amount of material equivalent to one Mount Everest each time it orbits its star. At this pace, given its small mass, the researchers predict that the planet may completely disintegrate in about 1 million to 2 million years.

“We got lucky with catching it exactly when it’s really going away,” says Avi Shporer, a collaborator on the discovery who is also at the TESS Science Office. “It’s like on its last breath.”

Hon and Shporer, along with their colleagues, will publish their results in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Their MIT co-authors include Saul Rappaport, Andrew Vanderburg, Jeroen Audenaert, William Fong, Jack Haviland, Katharine Hesse, Daniel Muthukrishna, Glen Petitpas, Ellie Schmelzer, Sara Seager, and George Ricker, along with collaborators from multiple other institutions.

An Unexpected Find

The new planet, which scientists have tagged as BD+05 4868 Ab, was detected almost by happenstance.

“We weren’t looking for this kind of planet,” Hon says. “We were doing the typical planet vetting, and I happened to spot this signal that appeared very unusual.”

The typical signal of an orbiting exoplanet looks like a brief dip in a light curve, which repeats regularly, indicating that a compact body such as a planet is briefly passing in front of, and temporarily blocking, the light from its host star.

This typical pattern was unlike what Hon and his colleagues detected from the host star BD+05 4868 A, located in the constellation of Pegasus. Though a transit appeared every 30.5 hours, the brightness took much longer to return to normal, suggesting a long trailing structure still blocking starlight. Even more intriguing, the depth of the dip changed with each orbit, suggesting that whatever was passing in front of the star wasn’t always the same shape or blocking the same amount of light.

What the Dust Tail Reveals

“The shape of the transit is typical of a comet with a long tail,” Hon explains. “Except that it’s unlikely that this tail contains volatile gases and ice as expected from a real comet — these would not survive long at such close proximity to the host star. Mineral grains evaporated from the planetary surface, however, can linger long enough to present such a distinctive tail.”

Given its proximity to its star, the team estimates that the planet is roasting at around 1,600 degrees Celsius, or close to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. As the star roasts the planet, any minerals on its surface are likely boiling away and escaping into space, where they cool into a long and dusty tail.

The dramatic demise of this planet is a consequence of its low mass, which is between that of Mercury and the moon. More massive terrestrial planets like the Earth have a stronger gravitational pull and therefore can hold onto their atmospheres. For BD+05 4868 Ab, the researchers suspect there is very little gravity to hold the planet together.

“This is a very tiny object, with very weak gravity, so it easily loses a lot of mass, which then further weakens its gravity, so it loses even more mass,” Shporer explains. “It’s a runaway process, and it’s only getting worse and worse for the planet.”

Rarest of the Rare

Of the nearly 6,000 planets that astronomers have discovered to date, scientists know of only three other disintegrating planets beyond our solar system. Each of these crumbling worlds were spotted over 10 years ago using data from NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. All three planets were spotted with similar comet-like tails. BD+05 4868 Ab has the longest tail and the deepest transits out of the four known disintegrating planets to date.

“That implies that its evaporation is the most catastrophic, and it will disappear much faster than the other planets,” Hon explains.

An Ideal Candidate for JWST

The planet’s host star is relatively close, and thus brighter than the stars hosting the other three disintegrating planets, making this system ideal for further observations using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which can help determine the mineral makeup of the dust tail by identifying which colors of infrared light it absorbs.

This summer, Hon and graduate student Nicholas Tusay from Penn State University will lead observations of BD+05 4868 Ab using JWST. “This will be a unique opportunity to directly measure the interior composition of a rocky planet, which may tell us a lot about the diversity and potential habitability of terrestrial planets outside our solar system,” Hon says.

Future Searches and Observations

The researchers will also look through TESS data for signs of other disintegrating worlds.

“Sometimes with the food comes the appetite, and we are now trying to initiate the search for exactly these kinds of objects,” Shporer says. “These are weird objects, and the shape of the signal changes over time, which is something that’s difficult for us to find. But it’s something we’re actively working on.”

Reference: “A Disintegrating Rocky Planet with Prominent Comet-like Tails around a Bright Star” by Marc Hon, Saul Rappaport, Avi Shporer, Andrew Vanderburg, Karen A. Collins, Cristilyn N. Watkins, Richard P. Schwarz, Khalid Barkaoui, Samuel W. Yee, Joshua N. Winn, Alex S. Polanski, Emily A. Gilbert, David R. Ciardi, Jeroen Audenaert, William Fong, Jack Haviland, Katharine Hesse, Daniel Muthukrishna, Glen Petitpas, Ellie Hadjiyska Schmelzer, Norio Narita, Akihiko Fukui, Sara Seager and George R. Ricker, 22 April 2025, The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/adbf21

This work was supported, in part, by NASA.

Auto-posted from news source